What does it mean to curate a design project in the frame of Climate Change? What are our responsibilities as curators, researchers and designers? How can we participate in challenging old assumptions and build novel narratives that go beyond a purely human-centred understanding of the world?

CURATING CHANGE proposes to look at curation as an act of care and activism, a process through which we can shape meaningful worldviews that take into consideration all beings and an instrument with which to raise critical questions and mediate issues linked to the current environmental and social crises.

The starting point of the workshop will be a series of vegetal-related pieces from the Dresden State Art Collection and plants from the botanical gardens of Pillnitz Park. Nourished by conversations with local specialists – Museum’s curators, gardeners, historians – we will study the stories of these artworks and plants, attempting to deconstruct and reframe them in light of contemporary reflections such as plants’ objectification and the idea of plants as intelligent and sentient beings, and as humans’ relationships with non-humans.

The Historical Park

•

Pillnitz Park houses one of the biggest varieties of non-native palm species in Germany, introduced by the Saxon Kings, who had an adornment for exotic and antique objects. Palm motifs appear in classical decor and Chinoiserie murals, symbolizing wealth during imperial times. However, these ornamental palms and objects often go unquestioned in museum displays.

How did past cultures perceive nature? How can museums encourage visitors to think critically about these displays? Beyond their exotic appeal, what are the origins of these plants?

Reflecting on my own memories of palm trees, I explore the ecological loss and grief experienced by the Mah Meri Meri people.

The Mah Meri, known as the “people of the forest”, have lived along Malaysia’s southwest coast for generations. Before the 1900s, they thrived in river estuaries and mainland forests, relying on both land and sea. They moved as needed, adapting to food sources and environmental changes.

However, during British colonial rule, their ancestral lands were cleared for coconut, rubber, coffee, and palm oil plantations. Mangrove forests were destroyed, and earthen bunds reshaped the coastline, devastating their fishing grounds and ecosystems.

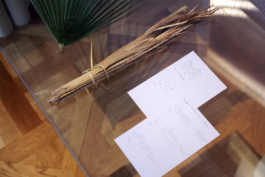

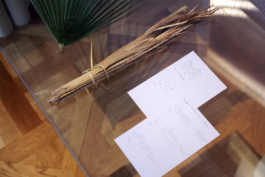

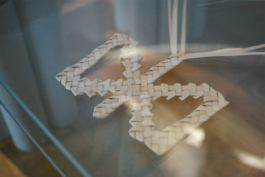

Chita’ Anyaman tells the story of ecological loss through woven palm leaves, depicting other-than-human entities. In 2019, during a field trip to Pulau Carey, I met Maznah Unyan, a master weaver of the Mah Meri. She taught me how to process and weave mengkuang (Pandanus amaryllifolius) leaves—a plant now scarce due to deforestation.

Inspired by traditional Mah Meri patterns, I created wearable weavings and sketches of mangrove flora and fauna, echoing the folk tales in Mah Meri Animal Folklores, published by Gerimis Art Project. Although the Mah Meri’s world may seem distant, their stories prompt us to reflect on our own ecosystems and the losses they endure.

For this project, I used dwarf palm leaves (Chamaerops humilis), native to Southwest Europe and found as ornamental plants in the Kunstgewerbemuseum.

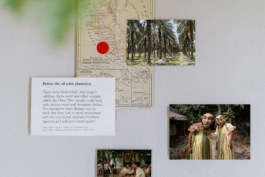

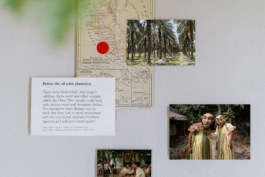

Before the oil palm plantation

•

There were birds (chip), deer (rusa’), wildboar (ketu meri) and other animals which the Mah Meri people could hunt with various traps and blowpipes (belau). The mangrove forest (bakau) was so thick that they had to avoid encounters with the occasional elephant (merhat), tigers (a-aa’) and even forest spirits!

~ Chita’ Hae: Culture, Crafts and Customs of the Mah Meri

in Kampung Sungai Bumbon, Pulau Carey

Exhibition opening of “Pleasure Garden” and activation weaving workshop with the children.

Many thanks to Gerimis Art, Reita Rahim, and Maznah Unyan for their advice on Mah Meri matters.

Image credit:

[1] Graphic by Natalia Milla

[2] Imagerie d'Épinal, n° 1674. Grand Théâtre Nouveau. Jardin d`Hiver – Fond, Épinal (Frankreich), nach 1889, Puppentheatersammlung

[3] Map shewing the British Dependencies, Malaysia Peninsula and Singapore (1888), British Library

[4] Palm oil plantation, Wikimedia Commons

[5-6] “Mah Meri girls get ready for dancing for tourists”, Carey Island, Bemboun Village, Carey Island, Malaysia, 1990, Jean Gaumy

[7, 10-12, 13] by Evey Kwong

[8-9] by Leonie Hochstrasser

What does it mean to curate a design project in the frame of Climate Change? What are our responsibilities as curators, researchers, and designers? How can we participate in challenging old assumptions and build novel narratives that go beyond a purely human-centred understanding of the world? CURATING CHANGE proposes to look at curation as an act of care and activism, a process through which we can shape meaningful worldviews that take into consideration all beings and an instrument with which to raise critical questions and mediate issues linked to the current environmental and social crises.

The starting point of the workshop will be a series of vegetal-related pieces from the Dresden State Art Collection and plants from the botanical gardens of Pillnitz Park. Nourished by conversations with local specialists – Museum’s curators, gardeners, historians – we will study the stories of these artworks and plants, attempting to deconstruct and reframe them in light of contemporary reflections such as plants’ objectification and the idea of plants as intelligent and sentient beings, and as humans’ relationships with non-humans.

The Historical Park

•

Pillnitz Park houses one of the biggest varieties of non-native palm species in Germany, introduced by the Saxon Kings, who had an adornment for exotic and antique objects. Palm motifs appear in classical decor and Chinoiserie murals, symbolizing wealth during imperial times. However, these ornamental palms and objects often go unquestioned in museum displays.

How did past cultures perceive nature? How can museums encourage visitors to think critically about these displays? Beyond their exotic appeal, what are the origins of these plants?

Reflecting on my own memories of palm trees, I explore the ecological loss and grief experienced by the Mah Meri people.

The Mah Meri, known as the “people of the forest”, have lived along Malaysia’s southwest coast for generations. Before the 1900s, they thrived in river estuaries and mainland forests, relying on both land and sea. They moved as needed, adapting to food sources and environmental changes.

However, during British colonial rule, their ancestral lands were cleared for coconut, rubber, coffee, and palm oil plantations. Mangrove forests were destroyed, and earthen bunds reshaped the coastline, devastating their fishing grounds and ecosystems.

Chita’ Anyaman tells the story of ecological loss through woven palm leaves, depicting other-than-human entities. In 2019, during a field trip to Pulau Carey, I met Maznah Unyan, a master weaver of the Mah Meri. She taught me how to process and weave mengkuang (Pandanus amaryllifolius) leaves – a plant now scarce due to deforestation.

Inspired by traditional Mah Meri patterns, I created wearable weavings and sketches of mangrove flora and fauna, echoing the folk tales in Mah Meri Animal Folklores, published by Gerimis. Although the Mah Meri’s world may seem distant, their stories prompt us to reflect on our own ecosystems and the losses they endure.

For this project, I used dwarf palm leaves (Chamaerops humilis), native to Southwest Europe and found as ornamental plants in the Kunstgewerbemuseum.

Before the oil palm plantation

•

There were birds (chip), deer (rusa’), wildboar (ketu meri) and other animals which the Mah Meri people could hunt with various traps and blowpipes (belau). The mangrove forest (bakau) was so thick that they had to avoid encounters with the occasional elephant (merhat), tigers (a-aa’) and even forest spirits!

~ Chita’ Hae: Culture, Crafts and Customs of the Mah Meri in Kampung Sungai Bumbon, Pulau Carey

Exhibition opening of “Pleasure Garden” and activation weaving session with the children.

•

Many thanks to Gerimis Art, Reita Rahim, and Maznah Unyan for their advice on Mah Meri matters.

Image credit:

[1] Graphic by Natalia Milla

[2] Imagerie d'Épinal, n° 1674. Grand Théâtre Nouveau. Jardin d`Hiver – Fond, Épinal (Frankreich), nach 1889, Puppentheatersammlung

[3] Map shewing the British Dependencies, Malaysia Peninsula and Singapore (1888), British Library

[4] Palm oil plantation, Wikimedia Commons

[5-6] “Mah Meri girls get ready for dancing for tourists”, Carey Island, Bemboun Village, Carey Island, Malaysia, 1990, Jean Gaumy

[7, 10-12, 13] by Evey Kwong

[8-9] by Leonie Hochstrasser