⭢ All vernacular terms are recorded verbally and might be inaccurate.

The Kelabit-Kerayan area is a high plateau lying between 800 and over 1,000 meters above sea level, at the border of eastern Sarawak and the northern tip of East Kalimantan. This plateau is home to a relatively homogeneous set of peoples, called Kelabit (Mashman) and generally referred to as Lun Dayeh in Kalimantan (Crain). The Lun Dayeh actually include groups called Lun Baa' (“people of the marshes”), or “people of the wet rice fields” (Padoch).

The basketry of the Kelabit-Kerayan people is unique, as were some of their traditional material culture and economic practices, due in part to their particularly isolated environment (Davy Ball).

Maintaining their adat (customs and traditions) and their unique identity is fundamental for the Dayak Lun Dayeh. So is religion. Eighty five per cent are Christian Protestant or Evangelical—a fact duly recorded on their national identity card. Since 1974, it is the church service that makes a marriage lawful.

There is a distinct partitioning of the adat (customary) and church ceremonies. The adat ceremony, the ritual exchange of bridewealth, includes the tayen and raung basung. Since the mass religious conversion of the late 1920s, the adat ceremonies are no longer used in a spiritual sense but rather as signifiers of Lun Dayeh identity (Macdonald with Kadok, Garland).

⭠ Ibu Mince, a visiting Agabag plaiter from the Sembakung area. She is demonstrating the bamboo splitting process.

The Rice Baskets

Picture credit to Margrit Linder

The Lun Dayeh women of the Krayan Highlands are some of the most innovative and meticulous bamboo and rattan plaiters in Indonesia.

For an object made from bamboo to last and resist rapid deterioration from insects, the plant must be harvested and treated in certain ways. Wherever usage of bamboo is widespread, village folk have developed traditional methods of harvesting, evolved from trial and error. It is said that the Lun Dayeh almost never harvest bamboo outside the period known as rondom and magalang. Rondom literally means ‘no moon’, a period of time when bamboo may produce greater amounts of cellulose and silica than of starch, the latter being food for insects.

Harvesting during magalang period, when the leaves of the bamboo drop, is also said to produce insect-resistant material. If forced to harvest at other times, village folks leach out bamboo stems or poles in fast-flowing streams for several days to remove their starch.

In Dayak culture, rice is closely associated with female fertility. As the repository for rice, the source of human life, the tayen is created and treated with great reverence. The spiritual association of rice with women means that traditionally women use the tayen for harvesting rice and it is the bride’s family that gives the tayen with the raung basung to the groom’s family. At the end of a day of harvest, the tayen and raung basung are stored in the rice barn, the raung basung closing the top of the tayen. In former times, they were an inseparable pair (Macdonald with Kadok, Garland).

From top left to bottom right:

1. The liquid extract from the pokok uber are used as a mordant before applying the deep black of the natural dye from the pot soot.

2. Dragon's blood resin is also produced from the rattan palms of the genus Daemonorops of the Indonesia and known as jerang. It is gathered by breaking off the layer of red resin encasing the unripe fruit of the rattan. The collected resin is then rolled into solid balls before being used.

3. Ibu Sumanti applying the mordant with help of the fire to melt the resin

4. Learning the basics of Dayak plaitwork patterns

5. Construction of the rim ‘bepen’ and strap fastener

Final step: Firing to pierce holes on rattan to form and fasten the ground structure.

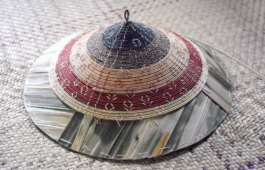

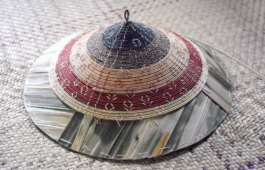

Raung Temar and Basung

Among the most distinctive productions of the Kerayan people is the raung basung hat. It comprises an inner layer of daun kaber (pandanus leaves), an outer layer made of rings of plant fibers sewn onto the inner layer with thread (combrang stems fibre), and a rattan rim. These fibres are procured primarily from the aerial prop roots (basung), of a tree-like species of pandanus or from the lower-quality kinangan (Eugeissona utilis, Christensen).

Lun Dayeh artisans are expert dyers. They make a range of natural dye colours out of plants from their local area. The kinangan is dye with ipang. Black dye is obtained from pot soot mixed with the sap of pokok uber. Displaced by shop paint, these traditional colors have fallen into disuse; also, contemporary tend to be made in a slightly smaller size.

The raung basung is made entirely from plant fibres—plaited pandanus combined with rattan, temar and kinangan.

The natural dyes used in the raung basung also differ from those of the river communities. Shades of green, pink, orange, brown and yellow are tastefully combined, sometimes contrasting, sometimes tonal. The artisans display unlimited creativity continually experimenting and reviving their natural dye recipes (Macdonald with Kadok, Garland).

⭡ Splitting pandanus leaves with an improvised fishing string.

⭠ Leaves of the same plant, ipang siaq, produce red and red-brown colours to dye the fibres made from temar leaves. If kinangan palm fibre is dyed the result is an orange rather than a pink colour. To make red the leaves of the ipang siaq are boiled with the temar fibre. To make the red-brown colour a combination of ipang siaq, ipang hitam and minir leaves are used. The leaves are boiled for 2-3 hours with the temar fibre.

Pounding ipang for the natural dye process. ⭢

⭠ Improvised skeining tool from a wok spatula and bodkin with a metal piece from an umbrella frame.

Within the vicinity of the village lies the abundance raw materials. In the early morning, it is swathed in mist—cool, green and every so slightly mystical. Kinangan, bamboo, temar and many other fibre plants grow abundantly here, and from it the Lun Dayeh women forage the material for weaving.

From top left to bottom right:

1. Combrang, a Malay-native plant, one of the most versatile plants used as source of food, medicine, and weaving material.

2. Kinangan, rattan and temar after dyeing process.

3. Ibu Sumanti skeining rattan with an improvised wok-spatula tool.

4. Ibu Saban twisting cordages from temar

5. Variety of natural plant dye on temar

6. Temar (Curculigo villosa). The fibrous leaves of this plant are used typically to make a soft headstrap (senguloh) used on harvesting, reaping, all-purpose, and burden baskets. The leaves are split into sections and plaited. The fiber within the leaves, which twists easily, can be processed to make a fine thread.

Dyeing fibers with dye plants is becoming rare in the community of my fieldwork, and even so, it is done on a much smaller scale compared to the past. Today, artificial dyes and paints are commonly used. They are easier to procure and to apply and offer a larger choice of colours for any kind of handicraft.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, coloured plastic fibres reclaimed from commercial packaging have made their entry as fibres for basketry and have become increasingly popular for all types of baskets. Plastic strings possess important qualities: they are strong and light, easy to work with, and they come in the brightest possible colours. Today it is no unusual to spot such baskets in the deep jungle (Sellato).

Typically in the developing world, the applications of plastic fibres differ from the developed world, and is seen as step to modernity (Sellato).

Bekang Kerawang

Bekang Kerawang is a typical burden basket used and made by male Dayak hunters.

In the pre-Christianity times, the division of labor among the Dayaks, whereby men went on headhunting raids while women stayed home and wove beautiful dyed baskets and textiles, has been developed into an ideology of gender role distinction. Both weaving and headhunting appear to be highly valued activities in which women and men compete with members of their own sex for prestige, which is validated by commensurate material prosperity.

Beauty is a high ideal for Lun Dayeh women, just as courage in head-hunting is a male ideal. These two gender-defining ideals are joined in the Lun Dayeh understanding of rice production (Richard Allen Drake).

Harvesting rattan is hard work and not particularly pleasant. Collecting is usually done by men who carry the rattan home coiled or cut into sections. The thorny outer skin is stripped to expose the shiny smooth layer, which is the choice material for the other layer of mats and baskets. The canes most sought after by local people are the rotan saga (Calamus causius). These lashings of cane vary in diameter but are seldom bigger than the sized of a pencil.

The rattan canes used unsplit for the cycloid weaving of burden baskets (bekang kerawang) are from the species ue angat and ue kusa (Calamus flabellatus) and ue rabun (Calamus javensis). These same rattans are split for the hexagonal weaving on a finer burden basket (bekang mata) and an all-purpose food-gathering basket, the kalang.

A variety of species can be split for finer work needed for the twill weaving of harvesting and reaping baskets (bu 'an, raing), daily use baskets (uyut), borders, lashing and shoulder straps (kela'ih). These are ue tak (Calamus caesius), ue kusa (Calamus flabellatus), ue pa 'it, ue toki (Calamus pogoncanthus) and ue lingan (Daemonorops sabu).

The rattan cane is harvested when the thorny leaf-sheaths begin to fall away, revealing the mature cane underneath. The cane is cut near the ground and is pulled down from the canopy, dragging it against tree trunks to discard the thorny leaf-sheaths. The immature crown is trimmed off and the harvested canes are brought back in coils or cut in pieces of the desired length. The cane can be split green and then dried before weaving. If it is not to be used immediately, it is soaked in water to prevent it from drying out and becoming too brittle. It is split using a knife and is smoothed by using a metal template called a peru, which is often made by piercing holes through the base of an empty milk tin. The rattan strands are pushed through the holes of varying sizes to obtain a uniform width of rattan strands as required (Mashman, Valerie and N. Patricia).

Sources

1. ‘Variation as Norm: Names, Meanings and Referents in Borneo Basketry Decoration’, Bernard Sellato

2. ‘Bridewealth of the Dayak Lundayeh’, Karen Macdonald and Paulus Kadok

3. ‘Plaited Arts from the Borneo Rainforest’, Bernard Sellato

4. ‘Agricultural practices of the Kerayan Lun Dayeh. Borneo Research Bulletin 15(1)’, Christine Padoch

5. ‘Baskets from the forest: Kelabit baskets of Long Peluan’, Valerie Mashman

6. ‘The Bidayuh of Sarawak, Gender Spirituality and Swiddens: in Shifting Cultivation and Environmental Change Indigenous People, Agriculture and Forest Conservation’, Valerie Mashman and Nayoi Patricia

7. ‘Fiber and dye plants in two longhouse communities’, Christensen Padoch

8. ‘Betek, Tali ngan Atap’ ‘Knots, String and Blades’: Production and Use of Organic Utility Objects by the Orang Ulu of Sarawak, Davy Ball

9. ‘The Lun Dayeh,’ World Within: the Ethnic Groups of Borneo, Jay Crain

10. ‘Ibanic Textile Weaving’, Richard Allen Drake

This expedition is made possible thanks to the kindred spirit Margrit Linder, a filmmaker, crafts revivalist and a friend.

Follow her passionate years of venture into documenting the Dayak Agabag plaiting here.

Plaited Arts of North Borneo

Learning from the Lun Dayeh

The Kelabit-Kerayan area is a high plateau lying between 800 and over 1,000 meters above sea level, at the border of eastern Sarawak and the northern tip of East Kalimantan. This plateau is home to a relatively homogeneous set of peoples, called Kelabit (Mashman) and generally referred to as Lun Dayeh in Kalimantan. (Crain) The Lun Dayeh actually include groups called Lun Baa' (“people of the marshes”), or “people of the wet rice fields” (Padoch).

The basketry of the Kelabit-Kerayan people is unique, as were some of their traditional material culture and economic practices, due in part to their particularly isolated environment (Davy Ball).

Maintaining their adat (customs and traditions) and their unique identity is fundamental for the Dayak Lun Dayeh. So is religion. Eighty five per cent are Christian Protestant or Evangelical—a fact duly recorded on their national identity card. Since 1974, it is the church service that makes a marriage lawful. There is a distinct partitioning of the adat (customary) and church ceremonies. The adat ceremony, the ritual exchange of bridewealth, includes the tayen and raung basung. Since the mass religious conversion of the late 1920s, the adat ceremonies are no longer used in a spiritual sense but rather as signifiers of Lun Dayeh identity (Macdonald with Kadok, Garland).

⭡ Ibu Mince, a visiting Agabag plaiter from the Sembakung area. She is demonstrating the bamboo splitting process.

The Rice Baskets

⭡ Picture credit to Margrit Linder

The Lun Dayeh women of the Krayan Highlands are some of the most innovative and meticulous bamboo and rattan plaiters in Indonesia.

For an object made from bamboo to last and resist rapid deterioration from insects, the plant must be harvested and treated in certain ways. Wherever usage of bamboo is widespread, village folk have developed traditional methods of harvesting, evolved from trial and error. It is said that the Lun Dayeh almost never harvest bamboo outside the period known as rondom and magalang. Rondom literally means ‘no moon’, a period of time when bamboo may produce greater amounts of cellulose and silica than of starch, the latter being food for insects.

Harvesting during magalang period, when the leaves of the bamboo drop, is also said to produce insect-resistant material. If forced to harvest at other times, village folks leach out bamboo stems or poles in fast-flowing streams for several days to remove their starch.

In Dayak culture, rice is closely associated with female fertility. As the repository for rice, the source of human life, the tayen is created and treated with great reverence. The spiritual association of rice with women means that traditionally women use the tayen for harvesting rice and it is the bride’s family that gives the tayen with the raung basung to the groom’s family. At the end of a day of harvest, the tayen and raung basung are stored in the rice barn, the raung basung closing the top of the tayen. In former times, they were an inseparable pair (Macdonald with Kadok, Garland).

⭡ The liquid extract from the pokok uber are used as a mordant before applying the deep black of the natural dye from the pot soot.

⭡ Dragon's blood resin is also produced from the rattan palms of the genus Daemonorops of the Indonesia and known as jerang. It is gathered by breaking off the layer of red resin encasing the unripe fruit of the rattan. The collected resin is then rolled into solid balls before being used.

⭡ Ibu Sumanti applying the mordant with help of the fire to melt the resin

⭡ Learning the basics of Dayak plaitwork patterns

⭡ Construction of the rim ‘bepen’ and strap fastener

⭡ Final step: Firing to pierce holes on rattan to form and fasten the ground structure.

Raung Temar and Basung

Among the most distinctive productions of the Kerayan people is the raung basung hat. It comprises an inner layer of daun kaber (pandanus leaves), an outer layer made of rings of plant fibers sewn onto the inner layer with thread (combrang stems fibre), and a rattan rim. These fibres are procured primarily from the aerial prop roots (basung), of a tree-like species of pandanus or from the lower-quality kinangan (Eugeissona utilis, Christensen).

Lun Dayeh artisans are expert dyers. They make a range of natural dye colours out of plants from their local area. The kinangan is dye with ipang. Black dye is obtained from pot soot mixed with the sap of pokok uber. Displaced by shop paint, these traditional colors have fallen into disuse; also, contemporary tend to be made in a slightly smaller size.

The raung basung is made entirely from plant fibres—plaited pandanus combined with rattan, temar and kinangan.

The natural dyes used in the raung basung also differ from those of the river communities. Shades of green, pink, orange, brown and yellow are tastefully combined, sometimes contrasting, sometimes tonal. The artisans display unlimited creativity continually experimenting and reviving their natural dye recipes (Macdonald with Kadok, Garland).

⭡ Splitting tool with an improvised fishing string.

⭡ Leaves of the same plant, ipang siaq, produce red and red-brown colours to dye the fibres made from temar leaves. If kinangan palm fibre is dyed the result is an orange rather than a pink colour. To make red the leaves of the ipang siaq are boiled with the temar fibre. To make the red-brown colour a combination of ipang siaq, ipang hitam and minir leaves are used. The leaves are boiled for 2-3 hours with the temar fibre.

⭡ Pounding ipang for the natural dye process.

⭡ Kinangan, rattan and temar after the dyeing process.

Within the vicinity of the village lies the abundance raw materials. In the early morning, it is swathed in mist—cool, green and every so slightly mystical. Kinangan, bamboo, temar and many other fibre plants grow abundantly here, and from it the Lun Dayeh women forage the material for weaving.

⭡ Combrang, a Malay-native plant, one of the most versatile plants used as source of food, medicine, and weaving material.

⭡ Ibu Sumanti skeining rattan with an improvised wok-spatula tool.

⭡ Improvised skeining tool with wok spatula and bodkin with a metal piece from an umbrella frame.

⭡ Temar (Curculigo villosa). The fibrous leaves of this plant are used typically to make a soft headstrap (senguloh) used on harvesting, reaping, all-purpose, and burden baskets. The leaves are split into sections and plaited. The fiber within the leaves, which twists easily, can be processed to make a fine thread.

⭡ Ibu Saban twisting cordages from temar.

⭡ Variety of natural plant dye on temar

Dyeing fibers with dye plants is becoming rare in the community of my fieldwork, and even so, it is done on a much smaller scale compared with the past. Today, artificial dyes and paints are commonly used. They are easier to procure and to apply and offer a larger choice of colours for any kind of handicraft.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, coloured plastic fibres reclaimed from commercial packaging have made their entry as fibres for basketry and have become increasingly popular for all types of baskets. Plastic strings possess important qualities: they are strong and light, easy to work with, and they come in the brightest possible colours. Today it is no unusual to spot such baskets in the deep jungle (Sellato).

Typically in the developing world, the applications of plastic fibres differ from the developed world, and is seen as step to modernity (Sellato).

Bekang Kerawang

Bekang Kerawang is a typical burden basket used mainly by male hunters of Dayak.

In the pre-Christianity times, the division of labor among the Dayaks, whereby men went on headhunting raids while women stayed home and wove beautiful dyed baskets and textiles, has been developed into an ideology of gender role distinction. Both weaving and headhunting appear to be highly valued activities in which women and men compete with members of their own sex for prestige, which is validated by commensurate material prosperity. Beauty is a high ideal for Lun Dayeh women, just as courage in head-hunting is a male ideal. These two gender-defining ideals are joined in the Lun Dayeh understanding of rice production (Richard Allen Drake).

Harvesting rattan is hard work and not particularly pleasant. Collecting is usually done by men who carry the rattan home coiled or cut into sections. The thorny outer skin is stripped to expose the shiny smooth layer, which is the choice material for the other layer of mats and baskets. The canes most sought after by local people are the rotan saga (Calamus causius). These lashings of cane vary in diameter but are seldom bigger than the sized of a pencil.

The rattan canes used unsplit for the cycloid weaving of burden baskets (bekang kerawang) are from the species ue angat and ue kusa (Calamus flabellatus) and ue rabun (Calamus javensis). These same rattans are split for the hexagonal weaving on a finer burden basket (bekang mata) and an all-purpose food-gathering basket, the kalang.

A variety of species can be split for finer work needed for the twill weaving of harvesting and reaping baskets (bu 'an, raing), daily use baskets (uyut), borders, lashing and shoulder straps (kela'ih). These are ue tak (Calamus caesius), ue kusa (Calamus flabellatus), ue pa 'it, ue toki (Calamus pogoncanthus) and ue lingan (Daemonorops sabu).

The rattan cane is harvested when the thorny leaf-sheaths begin to fall away, revealing the mature cane underneath. The cane is cut near the ground and is pulled down from the canopy, dragging it against tree trunks to discard the thorny leaf-sheaths. The immature crown is trimmed off and the harvested canes are brought back in coils or cut in pieces of the desired length. The cane can be split green and then dried before weaving. If it is not to be used immediately, it is soaked in water to prevent it from drying out and becoming too brittle. It is split using a knife and is smoothed by using a metal template called a peru, which is often made by piercing holes through the base of an empty milk tin. The rattan strands are pushed through the holes of varying sizes to obtain a uniform width of rattan strands as required (Mashman, Valerie and N. Patricia).

All vernacular terms are recorded verbally and might be inaccurate.

Sources

1. ‘Variation as Norm: Names, Meanings and Referents in Borneo Basketry Decoration’, Bernard Sellato

2. ‘Bridewealth of the Dayak Lundayeh’, Karen Macdonald and Paulus Kadok

3. ‘Plaited Arts from the Borneo Rainforest’, Bernard Sellato

4. ‘Agricultural practices of the Kerayan Lun Dayeh. Borneo Research Bulletin 15(1)’, Christine Padoch

5. ‘Baskets from the forest: Kelabit baskets of Long Peluan’, Valerie Mashman

6. ‘The Bidayuh of Sarawak, Gender Spirituality and Swiddens: in Shifting Cultivation and Environmental Change Indigenous People, Agriculture and Forest Conservation’, Valerie Mashman and Nayoi Patricia

7. ‘Fiber and dye plants in two longhouse communities’, Christensen Padoch

8. ‘Betek, Tali ngan Atap’ ‘Knots, String and Blades’: Production and Use of Organic Utility Objects by the Orang Ulu of Sarawak, Davy Ball

9. ‘The Lun Dayeh,’ World Within: the Ethnic Groups of Borneo, Jay Crain

10. ‘Ibanic Textile Weaving’, Richard Allen Drake

This expedition is made possible thanks to the kindred spirit Margrit Linder, a filmmaker, crafts revivalist and a friend. Follow her passionate years of venture into documenting the Dayak Agabag plaiting here.