Design research and exhibition making

2020–present

•

For a very long time, we have regarded our neighbours in Borneo as someone inherently different from another. We have established societies, languages, and mindsets that prevent us from experiencing the world any differently. We – you and I, animals, plants, organic, inorganic, rituals, artefacts, and so forth – not only share the space; together we create it in a mutual founding of wars, peaceful and colonial times. Can craft be a tool to connect people with their local ecology and to set the boundaries free? Can it be a method for forest literacy and teach us how to lead different lives?

CONNECTEDNESS proposes to look at Borneo society as an act of care and activism, a process by looking at indigenous ways of coexisting with nature, and adjacent meaningful worldviews that take into consideration the pasts or potential futures of the island.

The project depicts a series of woven pieces and audio-visual media from the field trips by Evey Kwong, a design researcher born in Malaysia, currently based in Berlin. Nourished by conversations with local indigenous people, crafts makers, and ethnographers, we will study what it means to be connected to the Earth, implying further societal development of how we will share its abundant resources among what is soon expected to be a population of 25 million, along with all other living organisms. The stories of these craft works and plants, attempting to deconstruct and reframe them in light of contemporary reflections that set Borneo with their fellow humans and non-humans as collaborators. The project may help us rediscover just how connected we are as humans, despite the divided territories.

The working hands

⭡ A still from a short film (Length: 00:02:58): The hands on procession by Ibu Lidia Sumbun from Kampung Sg. Utik, Ibu Sumanti, Ibu Saban and Pak Sujarwoh from Kampung Long Layu. → Watch the film

Close to the earth: The hands that reap, sow, and weave.

One of the most thought-provoking phenomena observed is the perception of time. Whenever I return from Borneo to an urban lifestyle, I am struck by the perception that time is divided into distinct phases: work, rest, and repetition.

An eloquent quote by Byung-Chul Han from his book ‘The Disappearance of Rituals’, “Rest has become a recovery from work and a preparation for further work. When rest becomes a form of recovery from work, as is the case for many today, it loses its specific ontological value. It no longer represents an independent, higher form of existence and degenerates into a derivative of work. Today’s compulsion to produce perpetuates work and thus eliminates that sacred silence. Life becomes entirely profane, desecrated.”

It is significant to note that in Western societies, including some developing countries in the East, the practice of crafts is often perceived as either a hobby or a professional activity. A hands-on activity by a layperson is often regarded as a luxury of leisure time.

If we could learn from the perspective of indigenous communities, craft is part of a ritual. A ritual is not necessarily a religious activity; it is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or the making of revered objects. It is a space to play and interact. To some extent, it is a means of cultural survival.

Rice culture

For people of Dayak groups, padi, or rice holds a noble position: Rice is not only their staple food, but it represents the core aspect of life, passed down through generations.

Baskets are created and treated with great reverence as repositories for rice and rituals. The notion of basketry ‘containing life’¹ is indisputable, particularly in the context of rice rituals. Most groups have their own distinctive baskets and non-basket artefacts crafted for sowing and/or harvesting padi. The generations of belief in the ‘semengat padi’ (spirit of paddy) have led them to perform rituals to maintain soil fertility, repel pests, and prevent the occurrence of natural disasters.²

In the context of modern agriculture, the concept of ‘nature’ is viewed as an entity that can be regulated by humans. These rice rituals and their underlying values may provide a solution to some of today’s environmental and social troubles. By retracing the origins of a ‘trouble’³, it can help us to understand how to deal with it.

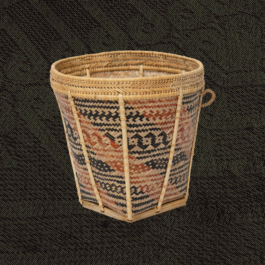

Object description:

[1] A “sintong”, a seed carrier made with rattan semut (body), Mukop (rim support), semambo (rim body), sega (woven rim), and tali temeran (basket strap). Learned from Ibu Lidia.

[2] A “ketam padi”, a rice harvesting tool

Source:

[1] A quote from Florina H. Capistrano-Baker (1998)

[2] An ethnographical insight from Hardiyanti

[3] Quoting Donna J. Haraway, “Our task is to make trouble, to stir up potent responses to devastating events, as well as to settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places.”

Abundance

Image description:

[1] Dragon’s blood resin from the rattan palms of the genus Daemonorops from the Lun Dayeh land. It is gathered by breaking off the layer of red resin encasing the unripe fruit of the rattan. The collected resin is then rolled into solid balls before being used.

[2] Ibu Sumanti is pounding plants in a wooden mortar for dyeing.

[3] Kinangan, rattan, and temar after the dyeing process.

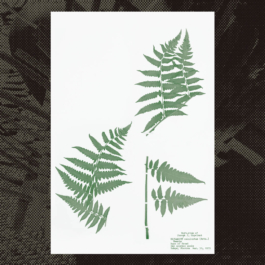

Plant as sentient beings

As humans simulate how plants and animals organize themselves through visual representations and motifs, is how humans can mimic the thinking, structure in nature and collaborate with them. Plants are objectified as long as we start to use and exploit them for our own interest. Far from being passive and ornamental, plants have evolved ingenious methods for dealing with whatever the world has thrown at them. As long as we are blinded by their exoticism, we will never come close to understanding plants as intelligent and sentient beings, or our relationship with other-than-humans.

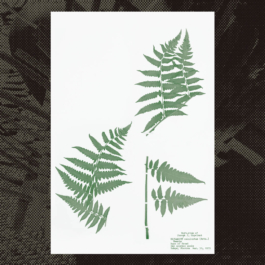

Image description:

[1] “Pakis” (Diplazium esculentum), New York Botanical Garden Steere Herbarium.

[2] “Buku”, a rice basket, motif from top to bottom: “impalilit” (lilit, Malay: wind), “nippon kapil” (fish teeth), a variation of “mata punai” (dove’s eye), dragon and “tinapak banong” (Pensiangan: jumping frog). Learned from Ibu Sumanti.

Forest Bonds

A place is woven of implicit stories: of history, culture, natural elements, materials, social relations, imaginings, and words.

In Sungai Utik of West Kalimantan province, at the border across Sarawak, and like many remote places in Kalimantan, craft is a language the Iban group has used to emphasise how forests and their ecologies are the fundamental premises for how the archipelago was shaped and continues to change with the influence of colonialism, human extractivism, and the New Capital vision.

As the forests are cleared for development and extractive activities, the soil eroses, the greenhouse gases increase in the atmosphere and they host problems for each of us on earth.

Each of the actors of a place are woven into many hidden systems and boundaries. If we could imagine these boundaries set free, we can discover how we are connected to the world and to the place we are at, allowing us to sense the complex world, where we exist in a mutual dependency with our surroundings.

Image description:

[1] Rotan Sega (Calamus caesius).

[2–3] Ibu Lidia harvesting rattan from the vicinity of Sungai Utik Longhouse.

ICAD 14th Edition: Unexpected

‘Special Appearance Region: Borneo’ for the

Indonesian Contemporary Art & Design [ICAD], Jakarta

Oct 10–Nov 10, 2024

UNEXPECTED, a place where artists and designers are invited to look into the history and present conditions of our society, and reformulate them with their imagination. As if lending the role of world-builders to them, they are invited to speculate on their relationship with the realities that surround them, to speculate on alternatives to the past, or possible futures. What should our concerns and creations gesture towards, given the distorted and unforeseen realities that surround us?

ICAD selects seven distinguished designers and cultural practitioners for ‘Special Appearance’ with the idea of honouring or paying tribute to their work. The category sheds light on Borneo as an island shared by both Indonesia and Malaysia. Reflections on the notion of crafts, borders, land, and environmental changes are highlighted through art, design, sound, and socially engaged works.

Curation by Amanda Ariawan and Prananda L. Malasan.

Exhibition design, research and writing by Evey Kwong.

Design research and exhibition making

2020–present

For a very long time, we have regarded our neighbours in Borneo as someone inherently different from another. We have established societies, languages, and mindsets that prevent us from experiencing the world any differently. We–you and I, animals, plants, organic, inorganic, rituals, artefacts, and so forth – not only share the space; together we create it in a mutual founding of wars, peaceful and colonial times. Can craft be a tool to connect people with their local ecology and to set the boundaries free? Can it be a method for forest literacy and teach us how to lead different lives?

CONNECTEDNESS proposes to look at Borneo society as an act of care and activism, a process by looking at indigenous ways of coexisting with nature, and adjacent meaningful worldviews that take into consideration the pasts or potential futures of the island.

The project depicts a series of woven pieces and audio-visual media from the field trips by Evey Kwong, a design researcher born in Malaysia, currently based in Berlin. Nourished by conversations with local indigenous people, crafts makers, and ethnographers, we will study what it means to be connected to the Earth, implying further societal development of how we will share its abundant resources among what is soon expected to be a population of 25 million, along with all other living organisms. The stories of these craft works and plants, attempting to deconstruct and reframe them in light of contemporary reflections that set Borneo with their fellow humans and non-humans as collaborators. The project may help us rediscover just how connected we are as humans, despite the divided territories.

The working hands

⭡ A still from a short film (Length: 00:02:58): The hands on procession by Ibu Lidia Sumbun from Kampung Sg. Utik, Ibu Sumanti, Ibu Saban and Pak Sujarwoh from Kampung Long Layu. → Watch the film

Close to the earth: The hands that reap, sow, and weave.

One of the most thought-provoking phenomena observed is the perception of time. Whenever I return from Borneo to an urban lifestyle, I am struck by the perception that time is divided into distinct phases: work, rest, and repetition.

An eloquent quote by Byung-Chul Han from his book ‘The Disappearance of Rituals’, “Rest has become a recovery from work and a preparation for further work. When rest becomes a form of recovery from work, as is the case for many today, it loses its specific ontological value. It no longer represents an independent, higher form of existence and degenerates into a derivative of work. Today’s compulsion to produce perpetuates work and thus eliminates that sacred silence. Life becomes entirely profane, desecrated.”

It is significant to note that in Western societies, including some developing countries in the East, the practice of crafts is often perceived as either a hobby or a professional activity. A hands-on activity by a layperson is often regarded as a luxury of leisure time.

If we could learn from the perspective of indigenous communities, craft is part of a ritual. A ritual is not necessarily a religious activity; it is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or the making of revered objects. It is a space to play and interact. To some extent, it is a means of cultural survival.

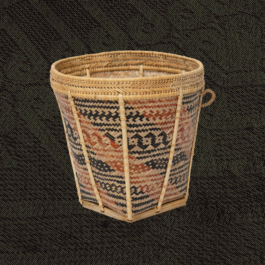

Rice culture

For people of Dayak groups, padi, or rice holds a noble position: Rice is not only their staple food, but it represents the core aspect of life, passed down through generations.

Baskets are created and treated with great reverence as repositories for rice and rituals. The notion of basketry ‘containing life’¹ is indisputable, particularly in the context of rice rituals. Most groups have their own distinctive baskets and non-basket artefacts crafted for sowing and/or harvesting padi. The generations of belief in the ‘semengat padi’ (spirit of paddy) have led them to perform rituals to maintain soil fertility, repel pests, and prevent the occurrence of natural disasters.²

In the context of modern agriculture, the concept of ‘nature’ is viewed as an entity that can be regulated by humans. These rice rituals and their underlying values may provide a solution to some of today’s environmental and social troubles. By retracing the origins of a ‘trouble’³, it can help us to understand how to deal with it.

Object description:

[1] A “sintong”, a seed carrier made with rattan semut (body), Mukop (rim support), semambo (rim body), sega (woven rim), and tali temeran (basket strap). Learned from Ibu Lidia.

[2] A “ketam padi”, a rice harvesting tool

Source:

[1] A quote from Florina H. Capistrano-Baker (1998)

[2] An ethnographical insight from Hardiyanti

[3] Quoting Donna J. Haraway, “Our task is to make trouble, to stir up potent responses to devastating events, as well as to settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places.”

Abundance

Image description:

[1] Dragon's blood resin from the rattan palms of the genus Daemonorops from the Lun Dayeh land. It is gathered by breaking off the layer of red resin encasing the unripe fruit of the rattan. The collected resin is then rolled into solid balls before being used.

[2] Ibu Sumanti pounding plants in a wooden mortar for dyeing.

[3] Kinangan, rattan and temar after the dyeing process.

Plant as sentient beings

As humans simulate how plants and animals organize themselves through visual representations and motifs, is how humans can mimic the thinking, structure in nature, and collaborate with them. Plants are objectified as long as we start to use and exploit them for our own interest. Far from being passive and ornamental, plants have evolved ingenious methods for dealing with whatever the world has thrown at them. As long as we are blinded by their exoticism, we will never come close to understanding plants as intelligent and sentient beings, or our relationship with other-than-humans.

Image description:

[1] “Pakis” (Diplazium esculentum), New York Botanical Garden Steere Herbarium.

[2] “Buku”, a rice basket, motif from top to bottom: “impalilit” (lilit, Malay: wind), “nippon kapil” (fish teeth), a variation of “mata punai” (dove’s eye), dragon, and “tinapak banong” (Pensiangan: jumping frog). Learned from Ibu Sumanti.

Forest Bonds

A place is woven of implicit stories: of history, culture, natural elements, materials, social relations, imaginings, and words.

In Sungai Utik of West Kalimantan province, at the border across Sarawak, and like many remote places in Kalimantan, craft is a language the Iban group has used to emphasise how forests and their ecologies are the fundamental premises for how the archipelago was shaped and continues to change with the influence of colonialism, human extractivism, and the New Capital vision.

As the forests are cleared for development and extractive activities, the soil eroses, the greenhouse gases increase in the atmosphere and they host problems for each of us on earth.

Each of the actors of a place are woven into many hidden systems and boundaries. If we could imagine these boundaries set free, we can discover how we are connected to the world and to the place we are at, allowing us to sense the complex world, where we exist in a mutual dependency with our surroundings.

Image description:

[1] Rotan Sega (Calamus caesius).

[2–3] Ibu Lidia harvesting rattan from the vicinity of Sungai Utik Longhouse.

UNEXPECTED, a place where artists and designers are invited to look into the history and present conditions of our society, and reformulate them with their imagination. As if lending the role of world-builders to them, they are invited to speculate on their relationship with the realities that surround them to speculate on alternatives to the past, or possible futures. What should our concerns and creations gesture towards, given the distorted and unforeseen realities that surround us?

ICAD selects seven distinguished designers and cultural practitioners for ‘Special Appearance’ with the idea of honouring or paying tribute to their work. The category sheds light on Borneo as an island shared by both Indonesia and Malaysia. Reflections on the notion of crafts, borders, land, and environmental changes are highlighted through art, design, sound, and socially engaged works.

Curation by Amanda Ariawan and Prananda L. Malasan.

Exhibition design, research and writing by Evey Kwong.