A field trip to Kampung Sting, Nyegol and Muk Ayun with curators, Catriona Maddocks and Sonia Luhong from Borneo Bengkel, to interrogate for a potential project involving ecological grief of the Bengoh Dam resettlement.

We were introduced to Lek (man on the left), a local Bidayuh farmer whose family, like many others in the Bengoh Valley, was impacted by the construction of the dam.

Lek tells about his memories of sounds, soil, his way of coping (and the inability to cope) with the changed environment and the stories of his ancestors, highlighting the deep connection to his community’s spiritual beliefs, particularly the role of paganism in their agricultural practices and the protective elements of their way of life.

Facts on the Bengoh Dam construction:

The construction not only led to the flooding of several villages, displacing 1,200 people from the Bidayuh community, but also caused severe environmental damage, affecting the natural landscape and the area’s biodiversity.

The dam construction also resulted in the loss of ancestral burial grounds, sacred sites, and cultural heritage for the indigenous communities. While the project was deemed necessary for urban development, the long-term social and environmental repercussions remain a point of ongoing debate.

The resettled Bidayuh villagers faced numerous challenges in adapting to their new environment. Many of them were farmers, and the new settlement areas were less fertile and lacked the infrastructure needed to sustain their traditional agricultural practices. Some also struggled to adjust to new ways of life and sources of income, as the new settlements did not offer the same opportunities as their original villages.

#BengohDam #EcologicalGrief #AncestralLand #EcologicalRestoration #ClimateAdaptation #HumanNonHuman #DesignActivism #Borneo

Revisiting the Mah Meri community of Pulau Carey to undertake a more in-depth ethnographic inquiry, focused on documenting the ecological loss and understanding how the community navigates the challenges of urbanisation alongside the traditional rituals and customs gradually slipping into memory.

More updates soon.

•

#MangroveEcologies #Deforestation #AncestralLand

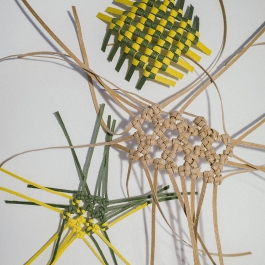

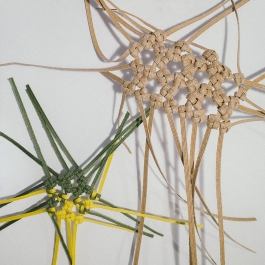

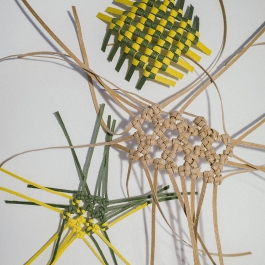

Creative Weaving Workshop

Textile Zentrum Haslach

21.–25.07.2025

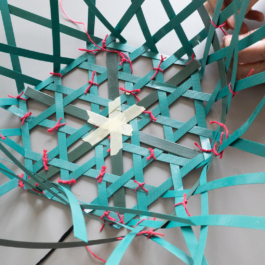

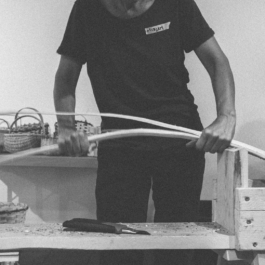

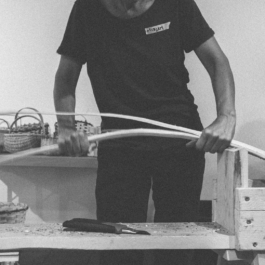

For this workshop, we explored endless possibilities of basket-weaving techniques with combinations of natural and alternative materials with a thematic approach.

The earliest baskets were made by coiling, twining, twisting and untwisting of plant fibres. Today, baskets are either niche-produced by craftspeople or overlooked as a craft practice. While basketry may no longer be relevant as a medium in and of itself, when combined with other media, it can cleverly hone problem-solving skills in a three-dimensional way.

We focused on coiling and plaiting weaving techniques. Following two days of hands-on and mental exercises, participants completed a final assignment, realised with techniques they have learned. During the work process, they were free to experiment with different approaches to connecting basket-weaving techniques with your discipline or a theme. Some made objects based on material experimentation, historical connections, the idea of repair and restoration, or your own design.

•

Participants: Rahel Graf, Stefanie Grünangerl, Brigitte Knell, Angela Koch-Maritsch, Andrea Kromoser, Ishmone Lubis, Sabine Meyer, Dominik Noger, Heidrun Picha, Karin Rowe, Rita Ströhm

Organization by Textile Zentrum Haslach

Teaching and workshop format by Evey Kwong

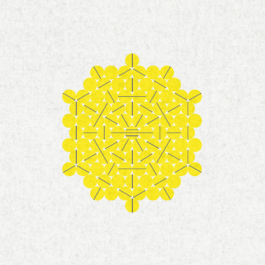

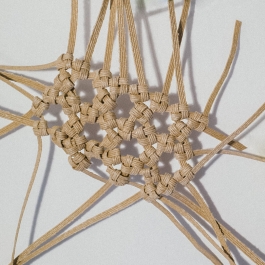

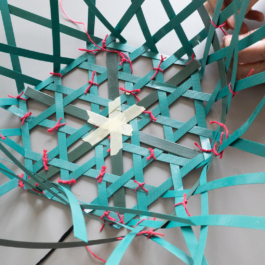

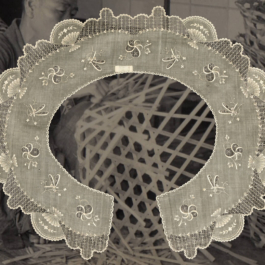

The triaxial weave has deep resonance across East and Southeast Asia, where weaving has never been just about material – it's a language of ancestry, community, and resilience.

From the bamboo fish traps of the Philippines to the finely patterned pandan mats of Malaysia, to the bold geometric rattan baskets of Indonesia and Thailand, the weave embodies both survival and artistry. By reimagining the weave in fabric paper with stitches that echo machine precision, the work bridges two inheritances: the handcraft traditions that grounded ancestry and new hybrid technique that defines the present.

The scallop edge stitch can be read as a contemporary nod to the scalloped trims of Southeast Asian textiles, like the piña edges in the Philippines or embroidered hems of Malay baju kurung. What was once bamboo and rattan becomes paper and thread – yet the gesture remains the same: honoring resourcefulness, adaptability, and artistry.

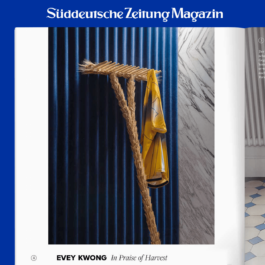

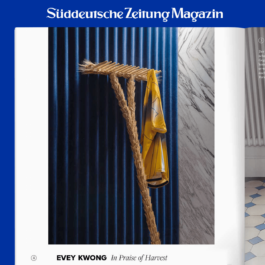

Evey Kwong’s work interweaves the past, present and future in a way. It's not so much about designing a product, she says, but about the values behind the production and the lost craft. For the rake, the Berlin-based designer has used Einkorn wheat, an ancient grain that she has bound using the same technique used to make harvest crowns for Thanksgiving. It stands for harvest, traditional agriculture and manual labour in the fields. “The rake is a symbol and a suggestion: it is important to work together with nature, as indigenous peoples do, instead of ruling over it as humans,” says Kwong.

Design Workshop

Schneeberg, Germany

23.09. – 27.09.2024

⭢ More on workshop

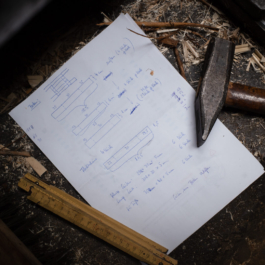

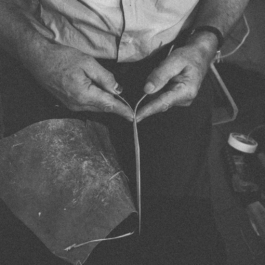

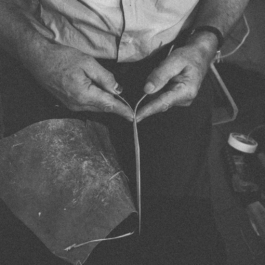

Chip basket making has existed in the region around Lauter and Bockau (Ore Mountains/Erzgebirge) since 1830. Before the invention of chip baskets, flexible spruce branches were woven into baskets, or the fine roots of the spruce trees were dug up because there were no willows in the Erzgebirge. This led to a ban on digging up tree roots, so they had to come up with something new – the chip basket. From 1830 onwards, more and more producers made chip baskets, mostly at home, with the help of children. In the 19th century, the chip baskets from the region around Lauter and Bockau were distributed internationally and were shipped as far as New York and London. Today, the craft is kept alive by Annette Rüffer and we will be learning from her.

Reimagining an everyday object

We created a series of completed exhibition-quality pieces, as well as expressive studies and prototypes that will be presented in two exhibitions in Ljubljana, Slovenia and in Schneeberg, Germany in 2025.

•

This workshop is funded by the European Union.

MADE IN partners are: Westsächsische Hochschule Zwickau (WHZ), @muozagreb, @oaza_kolektiv, @drugomore, @center_rog, @kunstgewerbemuseum.skd, @novaiskra, @maoslovenia / @czk_centerzakreativnost, Zenica City Museum, @passaaofuturo.

For many years I’ve been fascinated by basket made for rural use (popular baskets) simply for its beauty, ingenuity and its quality made to last. The character of the landscape that shape the objects, balancing necessity and (im)perfection. There is also the knowledge of reverse engineering in restauration processes that cleverly repair damages or solve mistakes during weaving because they are use objects. I think, design can learn so much from this knowledge.

Vedmeis basket is made of split hazel and willow rods. It was traditionally used for containing hay, wood and wool. Its special structure of two brackets form both the legs and handles of the basket. Additional stakes in the corners create a beautiful form.

The process of preparing the materials is the most labour intensive, it takes up the most time; 1/3 of the time for weaving.

Learned from Hege Iren Aasdal and Samson Øvstebø with support from one and only Akademie Flechtsommer Dalhausen.

One of the most valuable things I’ve learned during my recent trip to Cyprus, was the lost craft of Halloumi basket/sieve. These days, plastic sieves are used. While documenting the making of the traditional Cypriot hand broom, I discovered that the same vegetable fibre from the genus Juncus, with the local name, Sklinitzi (Το σκλινίτζι) is used for making baskets. Its stems are upright, very sharp and a lateral inflorescence placed on the top of the stem. The plant thrives in wetlands, areas with running water and streams.

Sklinitzia were particularly useful in basket weaving. Basket weaving is an art that many Cypriots knew in the old days and it was necessary, since the objects they made had various uses in everyday life. Today, there are very few people left who deal with the specific use of sklinitzia, because the traditional objects made from these natural materials have been replaced by other containers made of plastic.

The use of these basketry products, made from sklinitzia and other plants, may fell out of use but is still an answer to the use of plastics.

Coming soon : This research will be part of “Land of Brooms” publication which will be published in 2025.

Left to right

[1] Cypriot hand broom, Evey Kwong

[2] Juncus heldreichianus, N° PCPR018374, Herbier Pierre Coulot & Philippe Rabaute

[3] Halloumi baskets from Cyprus, Evey Kwong

A week-long exploratory trip to Sardinia allows me to uncover several natural materials which was to me before, unknown for weaving. Among others, asphodelus, mastic tree, myrtle, prickly pear, mauritania grass, wild olive tree and giant fennel. With its warm coastal temperature, the landscape is filled with Mediterranean shrubs and tall invasive plants, providing the local weavers with a wide variety of plant fibres and range of handicrafts. These include robust and rigid baskets, creels, sieves and sifters, as well as fine baskets.

•

Image depictions

[1] Asphodelus

[2] A potential biomaterial from a prickly pear

[3] Giant fennel

[4] Giant reed or cane

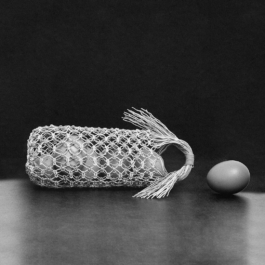

It was fortuitous that I was able to make contact with a fellow fishtrap/Nansa basket weaver, Giovanni Marongiu, through the intermediary of Henriette Waal from Atelier Luma. Giovanni grew up with his father, a fisherman, and has been making these fishtraps in different sizes for different fish and shellfish. As is the case with many obsolete crafts, the fishtrap has lost its original purpose. The ambiguous re-contextualised objects, which are produced for tourists as souvenirs, lamp shades and shopper baskets, fail to surpass the original utilitarian purpose of the technique. Consequently, they have lost their intrinsic value, despite their appeal to a niche market.

Su Cibiru, the traditional sieve of the Sardinian, has been used for generations to turn Gnocchi (Malloreddus) by hand. Malloreddus, sometimes Italianised as gnocchetti sardi, are a type of pasta typical of Sardinian cuisine. They have the shape of thin ribbed shells, made of semolina flour and water. The distinctive shape of Malloreddus is achieved through pressing the dough cubes against the end of a straw basket, called su cibiru (“the sieve”) in order to get them striped, or to have them smooth it was enough to simply press them against a wooden base.

Tracing the origin of this basket has reveals insights into how the industrialisation of pasta manufacturing has transformed this stapled food. Today, only a tiny proportion of the production process is handcrafted, which has resulted in the lost of this intricate sieve basket, and above all, a food culture.

“Of all the containers for food these are the most complex and difficult to make. The fibers used are various and are harvested in late spring, from April to the end of June. Usually cylindrical in shape with straight low walls, they are made up of three basic parts: the base, the filter and the sidewalls.

The base is a perfect circle, made from a length of bramble, elm or oleaster that forms the frame onto which the artifact develops. The filter of the sieve is made with reed stems within a woven mesh of very fine sedge fibers. The sidewalls are made of reeds, reaching a maximum height of 8 cm, distributed over a few concentric coils using a twisted stitch with a radial seam.” [1]

#lostcultures #originoffood

•

[1] Text via Museo dell'Intreccio Mediterraneo

From the fruit, thorny vines to leaves. Identifying and foraging different local species of wild rattan. To understand basketry as a craft is to understand the relationship between humans and the vegetal realm.

A utopic condition was set in place where one of the most protected areas and indigenous Iban community of resistance to illegal logging and palm oil production; West Borneo, Sungai Utik. Here, I am allowed to speak freely about the notion of abundance (rather than of scarcity), in the lens of indigenous stewardship and practices.

With the indigenous communities, respect towards nature is beyond the non-extractive model; understanding of how plants structure, behave and adopting them as allies and community resource (beyond profit).

I stopped using rattan some years back when I learned that this over-harvesting of ‘profitable crop’ has affected the forest health. When rattan is processed in the conventional way, toxic chemicals and petrol are used to process the materials.

These days, the occasions when I get to use rattan is only when I am in Borneo with the indigenous weavers or when I happen to find a sustainable source.

That is to say, these challenges are often never talked about in the crafts making business. The results of the forest products (fast crafts) are the main concern of the buyers and makers.

A labour and time consuming craft such as basket weaving has often been overlooked by the value of sustainable material sourcing and processing. To be able to experience and learn the indigenous way of crafts making remains a great experience for me until today.

“Baskets such as the quarter crans represented time and money to the carrier. The crans were baskets used to weigh and carry herring. Their measure has its origin in Scotland. The very word crann in Gaelic can mean a ‘measure for fresh herring’. Their size was regulated and standardized by government decree as a legal measure. From all points of view, it was very important that they were of a consistent size, or fishermen might be paid too little, or too much for their catch.”

The willows in between are bounded by waling and fitching. The weaving process is significant in the way the base and the border are all one bit of the willow. Short lengths of willow were used in the base so that, after it has been woven, the new lengths would be added and become the uprights and then form the top border of the basket.

To be precisely made, they had to be made by trained basket-makers. This cran shown in pictures is made by me based on the measurement from the great English basket-maker Colin Manthorpe with guidance from German basket-maker Rainer Groth. Rainer was fortunate to have met, acquainted and have acquired a cran from Colin before his passing.

#traditionalbasket #materialculture

Far right pictures and historical depiction © Woven Communities

“The Egmond carrier basket is typically made of brown and white willow, woven in a block pattern. It is a traditional basket used in the Egmond area until after the Second World War. The fishermen in Egmond called such a basket ‘Dreegmand’ (carrier basket) and they used it for all kinds of transport, including for beachcombing. In the past, the basket was also used to transport fish and shrimp.

‘Dreegmanden’ were made in three sizes, made by Alkmaar basket makers. The small sizes were used by the women and children to pick blackberries in the dunes. The farmers in Egmond within the dune area also used the carrier basket, under the name ‘kriel’. Remarkably, in Scotland the name ‘creel’ is known, but for a completely different type of basket.” ~ “van Wild naar Mand” by Piet-Hein Spieringhs

My version of the basket is improvised with a common oval base and curved body form. The original form is slightly conical with a Dutch-style base attached with a foot.

#traditionalbasket #ruralcraft

The Lost Basket Project

Learned from Jeanny Bouwen

Scale: 51 (w) x 55cm (h)

Material: Willow

I enjoy making country baskets rather than professionally made baskets for the reason of its puristic beauty and the humble tradition. There are many groundwork in country baskets to learn only with techniques themselves applied to their functionalities.

The form is inspired by Joe Hogan’s own turf basket from his traditional baskets archive.

Why is this a traditional basket since many willow techniques were widely used by basketmakers?

Because of the use of thick uprights, the base often warped, necessitating the use of a foot (a protective border underneath the basket that kept the base from touching the ground). A foot adds enormously to the length of time a basket will last and this technique was kept alive in Ireland by traditional rather than professional basketmakers.

#traditionalbasket #materialculture

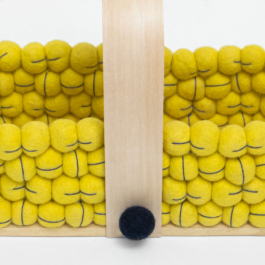

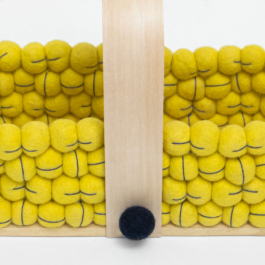

Commission for Basketclub x HAY

Material: Felt balls, Linden splint and spruce wood plate

Found object: Rice seed basket made of rattan, poran bamboo potentially dyed with plant sap, wood stripe (unknown)

Findspot: Chiang Dao

Acquired by Jeanny Bouwen

Play

A series of improvised torches using available and found plant materials. Going back before the invention of candles, the earliest form of artificial lighting used to illuminate an area were campfires or torches. Although it is convenient for us to acquire candles today, we often forget we are surrounded by materials which could be improvised to light up fire.

1. Torch made of damar gum wrapped in palm leaves.

2. Torch made of resin, bamboo leaves tied with raffia.

3. Torch composed of Zacaton roots soaked in fat or wax.

#materiality #lettherebelight #functionalobjects #resiliency #plantfibre #materialculture

Play

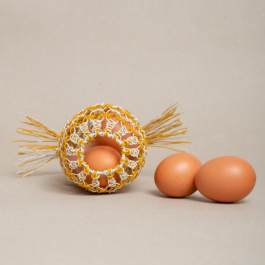

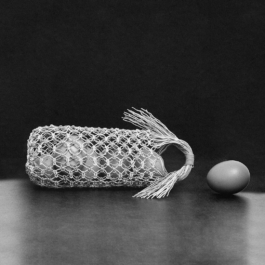

Material: Bell wires

How to wrap 5 eggs (haywirely), quoting the renowned Hideyuki Oka’s traditional Japanese packaging book.

Occasionally, I like doing things that are against my will, for example the Macramé knots. I often like playing with the limits of plasticity / elasticity of a material against a technique, in this case Macramé is usually implemented on soft materials.

As a result, my woven ode to Japanese traditional packaging aesthetic.

#newmaterials #newfunction

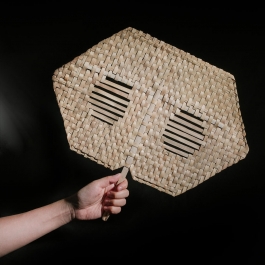

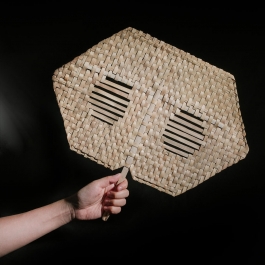

Masks have been used since antiquity for both ceremonial and practical purposes, as well as in the performing arts and for entertainment. A replicated mask becomes mere decorative effort and somewhat feels senseless unless it serves a culturally represented purpose. While making this mask, i began contemplating possibilities of introducing new forms which have not been represented by a particular culture. Can a new form and function (in this case a performative hand fan) be invented while keeping the use of natural materials?

View more works here.

#newfunction #performative #handfan

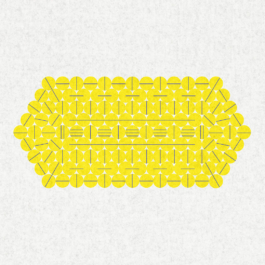

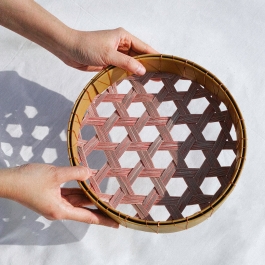

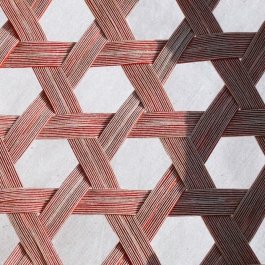

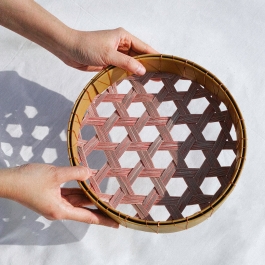

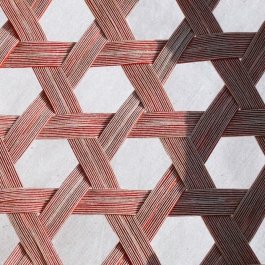

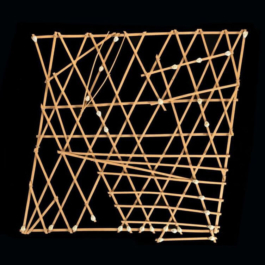

Inspired by the Japanese kagome weaving which bamboo is typically used for plaits construction, new material such as bronze wires are used to bind and sew the the rim and plaits together. The stripes are split with an improvised lo-tech device constructed with repurposed plywoods.

Works from all participants can be seen here.

#newmaterial #hexagonalplaiting

While contemplating the reinterpretation, I question the feasibility of the original material (rattan), fitting to the functional roots. I felt it was not appropriate to reconstruct any artifact without prior deeper consideration on the material culture origin and its use.

The basket is made out of curiosity with how far the technique could be expanded with its boundaries with the use of new materials and at the same time new technical parameters.

#newmaterials #materialculture #cycloidinterlacing #looping #borneo

•

Image credit to British Museum: Bekang Dechur by Kelabit ethnic group

•

#lattice #knot #geometry

While looking at these unique rice containers, i’ve figured that human evolution has hinted teaching is not essential for people to learn to make effective tools. The results counter established views about how human tools and technologies come to improve from generation to generation and point to an explanation for the extraordinary success of humans as a species. Although teaching is useful, it is not essential for cultural progress because people can use reasoning and reverse engineering of existing items to work out how to make tools.

The capacity to improve the efficacy of tools and technologies from generation to generation, known as cumulative culture, is unique to humans and has driven our ecological success. It has enabled us to inhabit the toughest and most remote regions on Earth and even have a permanent base in space. The way in which our cumulative culture has boomed compared to other species however remains a mystery.

While a knowledgeable teacher clearly brings important advantages, allowing students to independently create and design is more the crucial.

1 - Doll made of palm leaf, origin: Maluku, Indonesia

2 - Bottle made of rattan, origin: Madang, Papua New Guinea

3 - Pouch made of reed, origin: Palugama, Sri Lanka

4 - Bird-shaped pouch made of rush by Kenyah, origin: Sarawak

5 - Bottle made of palm leaf by Kenyah, origin: Sarawak

6 - Pouch made of palm leaf, origin: Rambah, Sumatra

Credit images to British Museum

Further play with square, pentagon and hexagonal construction of knots with Maori windmill knots. All materials thanks to Forces in Translation.

Forces in Translation works in the intersection of basketry, mathematics and anthropology. It is a Royal Society/Apex funded project, based in the UK.

Having so much fun making this! A further exploration with paper loops. This technique is inspired by Alison Martin's works.

•

#knots #coiling #fibonacci #geometry

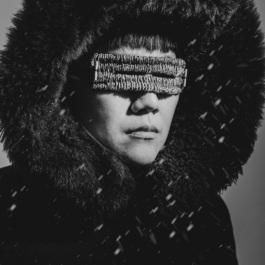

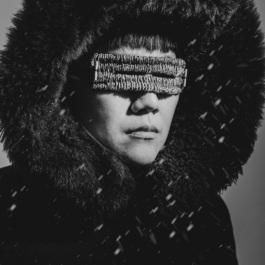

My first entry as a contribution to the club. Basketclub is an incredible group of designers and artists who use basket weaving techniques to experiment with materials and contexts.

Second image from the left, top: The Trustees of the British Museum. Snow goggles made by the Inuit / 1613699853, bottom: L.T. Burwash / Library and Archives Canada / PA-099362

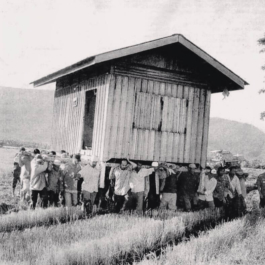

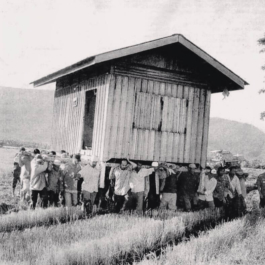

“Angkat Rumah” (lifting houses) was a form of physical relocation that was a common tradition practiced in kampungs as houses predominately consisted of wood. The structure of the house which is built with pillars makes it easy to be carried around. Depending on the size of the house, bamboo sticks are tied to the beam of the house to help lift it.

In the Malay and Filipino language there’s even its own term, ‘gotong royong’ and ‘bayanihan’, meaning the “community spirit”.

This tradition also fostered a sense of community, and originated when villagers wanted to move closer to their friends and family. Due to the increase of brick houses, it became easier to demolish than relocate. Therefore, this tradition has declined in popularity and is rarely practiced today.

The Spreewalders are sometimes superstitious and also practical. So it shows here with the wooden whisk. When the Christmas tree stands in the room for a long time, the wood of the trunk hardens and dries. Whorls were now carved from the ends of the sacred tree by shortening the branches and sawing off the whisk stick to the desired length. A new kitchen mixer is ready. Traditionally, these whorls were made to over 1 meter long.

Source CC-BY-NC-SA @ Museum des Landkreises Oberspreewald-Lausitz

These are Marshall Islands stick charts and they were made using the midrib of coconut fronds. The Marshall Islands are located in the Pacific Ocean within a region of islands known as Micronesia. Historically, the Malayo-Polynesian seafaring population from this part of the world used the stick chart as a kind of navigational device. But what the map visualises are not contours of land surface. Instead, the curving intersecting lines, supported by a skeletal framework, represent major ocean swells as well as how the location of islands, represented here with seashells, would change those wave patterns. Unlike how we rely on our Google map or Waze while driving on the road today, the charts were not used or consulted during a voyage. Instead, the information was memorised before embarking on a journey by an expert sailor who was trained to sense how the outrigger canoe would roll over the swell. Kinda like how Google map was used, well, before the advent of smartphones.

One of the handful of surviving rebbelib artifacts, currently on display at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Credit: DMNS and Malaysia Design Archive

Animals can be hypnotised in direct relation to their ability to concentrate their attention. While there seem to be no obvious reason for doing this, other than sheer entertainment value, the technique is in fact useful for farmers who need to slaughter a chicken, but do not have assistance at hand. It has also been said that the birds being relaxed beforehand, make more tender, tasty meat.

Suquamish basket maker, Ed Carriere explaining and performing the lost art of clam basketmaking.

A non-traditional woven sculpture teaching method by Artist Nathalie Miebach based on weather data collection.

With the introduction of guns in the 20th century, the need for group hunting for bear has diminished, leading to a decline in Matagi culture.

Explore book: The Hard Life by Jasper Morrison

First constructed in the marshes of what is now southern Iraq over 5,000 years ago, the ‘mudhif‘, the huge parabolic arched construction, is a unique local meeting place constructed entirely of reeds, straw and other natural materials.

Listen to Matthew Ngau Jau

The film was captured in Ethiopia by Gordon Clarke of the Institute of Nomadic Architecture.

Found knowledge

Extremely fascinating functional artifact:

Insect cage made in cycad leaf

via aguni archive

Found knowledge

“The world of our experience is, indeed, continually and endlessly coming into being around us as we weave. If it has a surface, it is like the surface of the basket: it has no ‘inside’ or ‘outside’. Mind is not above, nor nature below; rather, if we ask where mind is, it is in the weave of the surface itself. And it is within this weave that our projects of making, whatever they may be, are formulated and come to fruition. Only if we are capable of weaving, only then can we make.” — Tim Ingold

Listen to the sounds:

The Growth of Artifacts by Yannick Dauby

Creative Weaving Workshop

Textile Zentrum Haslach

21.–25.07.2025

For this workshop, we explored endless possibilities of basket-weaving techniques with combinations of natural and alternative materials with a thematic approach.

The earliest baskets were made by coiling, twining, twisting and untwisting of plant fibres. Today, baskets are either niche-produced by craftspeople or overlooked as a craft practice. While basketry may no longer be relevant as a medium in and of itself, when combined with other media, it can cleverly hone problem-solving skills in a three-dimensional way.

We focused on coiling and plaiting weaving techniques. Following two days of hands-on and mental exercises, participants completed a final assignment, realised with techniques they have learned. During the work process, they were free to experiment with different approaches to connecting basket-weaving techniques with your discipline or a theme. Some made objects based on material experimentation, historical connections, the idea of repair and restoration, or your own design.

•

Participants: Rahel Graf, Stefanie Grünangerl, Brigitte Knell, Angela Koch-Maritsch, Andrea Kromoser, Ishmone Lubis, Sabine Meyer, Dominik Noger, Heidrun Picha, Karin Rowe, Rita Ströhm

Organization by Textile Zentrum Haslach

Teaching and workshop format by Evey Kwong

Facts on the Bengoh Dam construction:

The construction not only led to the flooding of several villages, displacing 1,200 people from the Bidayuh community, but also caused severe environmental damage, affecting the natural landscape and the area’s biodiversity.

The dam construction also resulted in the loss of ancestral burial grounds, sacred sites, and cultural heritage for the indigenous communities. While the project was deemed necessary for urban development, the long-term social and environmental repercussions remain a point of ongoing debate.

The resettled Bidayuh villagers faced numerous challenges in adapting to their new environment. Many of them were farmers, and the new settlement areas were less fertile and lacked the infrastructure needed to sustain their traditional agricultural practices. Some also struggled to adjust to new ways of life and sources of income, as the new settlements did not offer the same opportunities as their original villages.

•

#BengohDam #EcologicalGrief #AncestralLand #EcologicalRestoration #ClimateAdaptation #HumanNonHuman #DesignActivism #Borneo

Revisiting the Mah Meri community of Pulau Carey to undertake a more in-depth ethnographic inquiry, focused on documenting the ecological loss and understanding how the community navigates the challenges of urbanisation alongside the traditional rituals and customs gradually slipping into memory.

More updates soon.

•

#MangroveEcologies #Deforestation #AncestralLand

Evey Kwong’s work interweaves the past, present and future in a way. It's not so much about designing a product, she says, but about the values behind the production and the lost craft. For the rake, the Berlin-based designer has used Einkorn wheat, an ancient grain that she has bound using the same technique used to make harvest crowns for Thanksgiving. It stands for harvest, traditional agriculture and manual labour in the fields. “The rake is a symbol and a suggestion: it is important to work together with nature, as indigenous peoples do, instead of ruling over it as humans,” says Kwong.

•

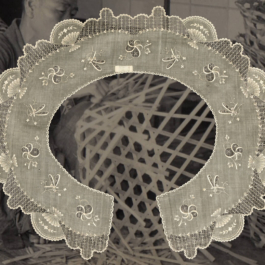

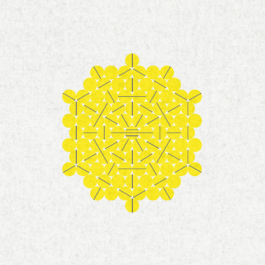

The triaxial weave has deep resonance across East and Southeast Asia, where weaving has never been just about material – it's a language of ancestry, community, and resilience.

From the bamboo fish traps of the Philippines to the finely patterned pandan mats of Malaysia, to the bold geometric rattan baskets of Indonesia and Thailand, the weave embodies both survival and artistry. By reimagining the weave in fabric paper with stitches that echo machine precision, the work bridges two inheritances: the handcraft traditions that grounded ancestry and new hybrid technique that defines the present.

The scallop edge stitch can be read as a contemporary nod to the scalloped trims of Southeast Asian textiles, like the piña edges in the Philippines or embroidered hems of Malay baju kurung. What was once bamboo and rattan becomes paper and thread – yet the gesture remains the same: honoring resourcefulness, adaptability, and artistry.

Design Workshop

Schneeberg, Germany

23.09. – 27.09.2024

⭢ More on workshop

Chip basket making has existed in the region around Lauter and Bockau (Ore Mountains/Erzgebirge) since 1830. Before the invention of chip baskets, flexible spruce branches were woven into baskets, or the fine roots of the spruce trees were dug up because there were no willows in the Erzgebirge. This led to a ban on digging up tree roots, so they had to come up with something new – the chip basket. From 1830 onwards, more and more producers made chip baskets, mostly at home, with the help of children. In the 19th century, the chip baskets from the region around Lauter and Bockau were distributed internationally and were shipped as far as New York and London. Today, the craft is kept alive by Annette Rüffer and we will be learning from her.

We created a series of completed exhibition-quality pieces, as well as expressive studies and prototypes that will be presented in two exhibitions in Ljubljana, Slovenia and in Schneeberg, Germany in 2025.

•

This workshop is funded by the European Union. MADE IN partners are: Westsächsische Hochschule Zwickau (WHZ), @muozagreb, @oaza_kolektiv, @drugomore, @center_rog, @kunstgewerbemuseum.skd, @novaiskra, @maoslovenia / @czk_centerzakreativnost, Zenica City Museum, @passaaofuturo.

For many years I’ve been fascinated by basket made for rural use (popular baskets) simply for its beauty, ingenuity and its quality made to last. The character of the landscape that shape the objects, balancing necessity and (im)perfection. There is also the knowledge of reverse engineering in restauration processes that cleverly repair damages or solve mistakes during weaving because they are use objects. I think, design can learn so much from this knowledge.

Vedmeis basket is made of split hazel and willow rods. It was traditionally used for containing hay, wood and wool. Its special structure of two brackets form both the legs and handles of the basket. Additional stakes in the corners create a beautiful form.

The process of preparing the materials is the most labour intensive, it takes up the most time; 1/3 of the time for weaving.

•

Learned from Hege Iren Aasdal and Samson Øvstebø with support from one and only Akademie Flechtsommer Dalhausen.

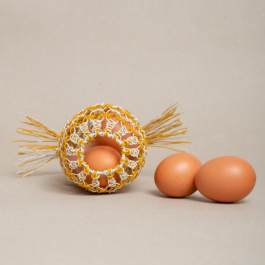

One of the most valuable things I’ve learned during my recent trip to Cyprus, was the lost craft of Halloumi basket/sieve. These days, plastic sieves are used. While documenting the making of the traditional Cypriot hand broom, I discovered that the same vegetable fibre from the genus Juncus, with the local name, Sklinitzi (Το σκλινίτζι) is used for making baskets. Its stems are upright, very sharp and a lateral inflorescence placed on top of the stem. The plant thrives in wetlands, areas with running water and streams.

Sklinitzia were particularly useful in basket weaving. Basket weaving is an art that many Cypriots knew in the old days and it was necessary, since the objects they made had various uses in everyday life. Today, there are very few people left who deal with the specific use of sklinitzia, because the traditional objects made from these natural materials have been replaced by other containers made of plastic.

The use of these basketry products, made from sklinitzia and other plants, may fell out of use but is still an answer to the use of plastics.

Coming soon : This research will be part of “Land of Brooms” publication which will be published in 2025.

•

Left to right

[1] Cypriot hand broom, Evey Kwong

[2] Juncus heldreichianus, N° PCPR018374, Herbier Pierre Coulot & Philippe Rabaute

[3] Halloumi baskets from Cyprus, Evey Kwong

A week-long exploratory trip to Sardinia allows me to uncover several natural materials which was to me before, unknown for weaving. Among others, asphodelus, mastic tree, myrtle, prickly pear, mauritania grass, wild olive tree and giant fennel. With its warm coastal temperature, the landscape is filled with Mediterranean shrubs and tall invasive plants, providing the local weavers with a wide variety of plant fibres and range of handicrafts. These include robust and rigid baskets, creels, sieves and sifters, as well as fine baskets.

•

Image depictions

[1] Asphodelus

[2] A potential biomaterial from a prickly pear

[3] Giant fennel

[4] Giant reed or cane

It was fortuitous that I was able to make contact with a fellow fishtrap/Nansa basket weaver, Giovanni Marongiu, through the intermediary of Henriette Waal from Atelier Luma. Giovanni grew up with his father, a fisherman, and has been making these fishtraps in different sizes for different fish and shellfish. As is the case with many obsolete crafts, the fishtrap has lost its original purpose. The ambiguous re-contextualised objects, which are produced for tourists as souvenirs, lamp shades and shopper baskets, fail to surpass the original utilitarian purpose of the technique. Consequently, they have lost their intrinsic value, despite their appeal to a niche market.

Su Cibiru, the traditional sieve of the Sardinian, has been used for generations to turn Gnocchi (Malloreddus) by hand. Malloreddus, sometimes Italianised as gnocchetti sardi, are a type of pasta typical of Sardinian cuisine. They have the shape of thin ribbed shells, made of semolina flour and water. The distinctive shape of Malloreddus is achieved through pressing the dough cubes against the end of a straw basket, called su cibiru (“the sieve”) in order to get them striped, or to have them smooth it was enough to simply press them against a wooden base.

Tracing the origin of this basket has reveals insights into how the industrialisation of pasta manufacturing has transformed this stapled food. Today, only a tiny proportion of the production process is handcrafted, which has resulted in the lost of this intricate sieve basket, and above all, a food culture.

“Of all the containers for food these are the most complex and difficult to make. The fibers used are various and are harvested in late spring, from April to the end of June. Usually cylindrical in shape with straight low walls, they are made up of three basic parts: the base, the filter and the sidewalls.

The base is a perfect circle, made from a length of bramble, elm or oleaster that forms the frame onto which the artifact develops. The filter of the sieve is made with reed stems within a woven mesh of very fine sedge fibers. The sidewalls are made of reeds, reaching a maximum height of 8 cm, distributed over a few concentric coils using a twisted stitch with a radial seam.” [1]

#lostcultures #originoffood

•

[1] Text via Museo dell'Intreccio Mediterraneo

From the fruit, thorny vines to leaves. Identifying and foraging different local species of wild rattan. To understand basketry as a craft is to understand the relationship between humans and the vegetal realm.

A utopic condition was set in place where one of the most protected areas and indigenous Iban community of resistance to illegal logging and palm oil production; West Borneo, Sungai Utik. Here, I am allowed to speak freely about the notion of abundance (rather than of scarcity), in the lens of indigenous stewardship and practices.

With the indigenous communities, respect towards nature is beyond the non-extractive model; understanding of how plants structure, behave and adopting them as allies and community resource (beyond profit).

I stopped using rattan some years back when I learned that this over-harvesting of ‘profitable crop’ has affected the forest health. When rattan is processed in the conventional way, toxic chemicals and petrol are used to process the materials.

These days, the occasions when I get to use rattan is only when I am in Borneo with the indigenous weavers or when I happen to find a sustainable source.

That is to say, these challenges are often never talked about in the crafts making business. The results of the forest products (fast crafts) are the main concern of the buyers and makers.

A labour and time consuming craft such as basket weaving has often been overlooked by the value of sustainable material sourcing and processing. To be able to experience and learn the indigenous way of crafts making remains a great experience for me until today.

“Baskets such as the quarter crans represented time and money to the carrier. The crans were baskets used to weigh and carry herring. Their measure has its origin in Scotland. The very word crann in Gaelic can mean a ‘measure for fresh herring’. Their size was regulated and standardized by government decree as a legal measure. From all points of view, it was very important that they were of a consistent size, or fishermen might be paid too little, or too much for their catch.”

The willows in between are bounded by waling and fitching. The weaving process is significant in the way the base and the border are all one bit of the willow. Short lengths of willow were used in the base so that, after it has been woven, the new lengths would be added and become the uprights and then form the top border of the basket.

To be precisely made, they had to be made by trained basket-makers. This cran shown in pictures is made by me based on the measurement from the great English basket-maker Colin Manthorpe with guidance from German basket-maker Rainer Groth. Rainer was fortunate to have met, acquainted and have acquired a cran from Colin before his passing.

#traditionalbasket #materialculture

Far right pictures and historical depiction © Woven Communities

“The Egmond carrier basket is typically made of brown and white willow, woven in a block pattern. It is a traditional basket used in the Egmond area until after the Second World War. The fishermen in Egmond called such a basket ‘Dreegmand’ (carrier basket) and they used it for all kinds of transport, including for beachcombing. In the past, the basket was also used to transport fish and shrimp.

‘Dreegmanden’ were made in three sizes, made by Alkmaar basket makers. The small sizes were used by the women and children to pick blackberries in the dunes. The farmers in Egmond within the dune area also used the carrier basket, under the name ‘kriel’. Remarkably, in Scotland the name ‘creel’ is known, but for a completely different type of basket.” ~ “van Wild naar Mand” by Piet-Hein Spieringhs

My version of the basket is improvised with a common oval base and curved body form. The original form is slightly conical with a Dutch-style base attached with a foot.

#traditionalbasket #ruralcraft

I enjoy making country baskets rather than professionally made baskets for the reason of its puristic beauty and the humble tradition. There are many groundwork in country baskets to learn only with techniques themselves applied to their functionalities.

The form is inspired by Joe Hogan’s own turf basket from his traditional baskets archive.

Why is this a traditional basket since many willow techniques were widely used by basketmakers?

Because of the use of thick uprights, the base often warped, necessitating the use of a foot (a protective border underneath the basket that kept the base from touching the ground). A foot adds enormously to the length of time a basket will last and this technique was kept alive in Ireland by traditional rather than professional basketmakers.

#traditionalbasketry #materialculture

Commission for Basketclub x HAY

Material: Felt balls, Linden splint and spruce wood plate

Found object: Rice seed basket made of rattan, poran bamboo potentially dyed with plant sap, wood stripe (unknown)

Findspot: Chiang Dao

Acquired by Jeanny Bouwen

Play

A series of improvised torches using available and found plant materials. Going back before the invention of candles, the earliest form of artificial lighting used to illuminate an area were campfires or torches. Although it is convenient for us to acquire candles today, we often forget we are surrounded by materials which could be improvised to light up fire.

1 – Torch made of damar gum wrapped in palm leaves

2 – Torch made of resin, bamboo leaves tied with raffia

3 – Torch composed of Zacaton roots soaked in fat or wax

#materiality #lettherebelight #functionalobjects #resiliency #plantfibre #materialculture

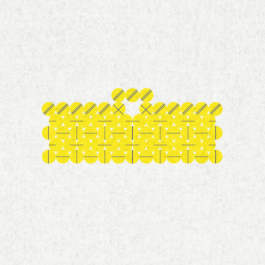

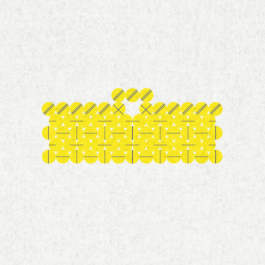

Material: Bell wires

How to wrap 5 eggs (haywirely), quoting the renowned Hideyuki Oka’s traditional Japanese packaging book.

Occasionally, I like doing things that are against my will, for example the Macramé knots. I often like playing with the limits of plasticity / elasticity of a material against a technique, in this case Macramé is usually implemented on soft materials.

As a result, my woven ode to Japanese traditional packaging aesthetic.

#newmaterials #newfunction

Masks have been used since antiquity for both ceremonial and practical purposes, as well as in the performing arts and for entertainment. A replicated mask becomes mere decorative effort and somewhat feels senseless unless it serves a culturally represented purpose. While making this mask, i began contemplating possibilities of introducing new forms which have not been represented by a particular culture. Can a new form and function (in this case a performative hand fan) be invented while keeping the use of natural materials?

View more works here.

#newfunction #performative #handfan

Inspired by the Japanese kagome weaving which bamboo is typically used for plaits construction, new material such as bronze wires are used to bind and sew the the rim and plaits together. The stripes are split with an improvised lo-tech device constructed with repurposed plywoods.

Works from all participants can be seen here.

#newmaterial #hexagonalplaiting

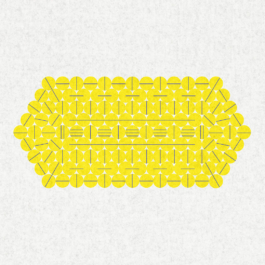

A reinterpretation of Bornean burden basket (Bekang) using cycloid open weave( Kerawang).

Traditionally, the basket is made using rattan. Cycloid is a technique I’ve been documenting and analyzing since my research trip in Borneo in 2020.

While contemplating the reinterpretation, I question the feasibility of the original material (rattan), fitting to the functional roots. I felt it was not appropriate to reconstruct any artifact without prior deeper consideration on the material culture origin and its use.

The basket is made out of curiosity with how far the technique could be expanded with its boundaries with the use of new materials and at the same time new technical parameters.

#newmaterials #materialculture #cycloidinterlacing #looping #borneo

Image credit to British Museum: Bekang Dechur by Kelabit ethnic group

Further play with square, pentagon and hexagonal construction of knots with Maori windmill knots. All materials thanks to Forces in Translation.

Forces in Translation works in the intersection of basketry, mathematics and anthropology. It is a Royal Society/Apex funded project, based in the UK.

1 – Doll made of palm leaf, origin: Maluku, Indonesia

2 – Bottle made of rattan, origin: Madang, Papua New Guinea

3 – Pouch made of reed, origin: Palugama, Sri Lanka

4 – Bird-shaped pouch made of rush by Kenyah, origin: Sarawak

5 – Bottle made of palm leaf by Kenyah, origin: Sarawak

6 – Pouch made of palm leaf, origin: Rambah, Sumatra

Images extracted from British Museum

Having so much fun making this! A further exploration with paper loops. This technique is inspired by Alison Martin's works.

#knots #coiling #fibonacci #geometry

My first entry as a contribution to the club. Basketclub is an incredible group of designers and artists who use basket weaving techniques to experiment with materials and contexts.

•

Second image from the left, top: The Trustees of the British Museum. Snow goggles made by the Inuit / 1613699853, bottom: L.T. Burwash / Library and Archives Canada / PA-099362

Quad node weaving, compressable. Technique from Alison Martin.

#lattice #knot #geometry

“Angkat Rumah” (lifting houses) was a form of physical relocation that was a common tradition practiced in kampungs as houses predominately consisted of wood. The structure of the house which is built with pillars makes it easy to be carried around. Depending on the size of the house, bamboo sticks are tied to the beam of the house to help lift it.

In the Malay and Filipino language there’s even its own term, ‘gotong royong’ and ‘bayanihan’, meaning the “community spirit”.

This tradition also fostered a sense of community, and originated when villagers wanted to move closer to their friends and family. Due to the increase of brick houses, it became easier to demolish than relocate. Therefore, this tradition has declined in popularity and is rarely practiced today.

The Spreewalders are sometimes superstitious and also practical. So it shows here with the wooden whisk. When the Christmas tree stands in the room for a long time, the wood of the trunk hardens and dries. Whorls were now carved from the ends of the sacred tree by shortening the branches and sawing off the whisk stick to the desired length. A new kitchen mixer is ready. Traditionally, these whorls were made to over 1 meter long. Source CC-BY-NC-SA @ Museum des Landkreises Oberspreewald-Lausitz

Found knowledge

These are Marshall Islands stick charts and they were made using the midrib of coconut fronds. The Marshall Islands are located in the Pacific Ocean within a region of islands known as Micronesia. Historically, the Malayo-Polynesian seafaring population from this part of the world used the stick chart as a kind of navigational device. But what the map visualises are not contours of land surface. Instead, the curving intersecting lines, supported by a skeletal framework, represent major ocean swells as well as how the location of islands, represented here with seashells, would change those wave patterns. Unlike how we rely on our Google map or Waze while driving on the road today, the charts were not used or consulted during a voyage. Instead, the information was memorised before embarking on a journey by an expert sailor who was trained to sense how the outrigger canoe would roll over the swell. Kinda like how Google map was used, well, before the advent of smartphones.

One of the handful of surviving rebbelib artifacts, currently on display at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Credit: DMNS and Malaysia Design Archive

Weaving origin: Portugal

Material: Esparto

Length of cord: 6m

NORTHERN LUZON HATS

Found knowledge

⭢ Link

Pictures credit to Penn Museum

Animals can be hypnotised in direct relation to their ability to concentrate their attention. While there seem to be no obvious reason for doing this, other than sheer entertainment value, the technique is in fact useful for farmers who need to slaughter a chicken, but do not have assistance at hand. It has also been said that the birds being relaxed beforehand, make more tender, tasty meat.

With special knotted cords, data were stored until the 20th century on the Japanese Ryukyu Islands. With rice straw, nodes were arranged according to a certain system and represent quantities in the decimal system. This made it easy to record information without knowing the characters.

A similar method is also known by the Inca Empire. There, the cords (Quipu) were used for records in the administration, with which religious, chronological and statistical data were stored. For bookkeeping, especially the understanding of the individual calculation steps and to make sense for the intermediate results.

Artefact from Okinawa, 1930

Suquamish basket maker, Ed Carriere explaining and performing the lost art of clam basket making.

A non-traditional woven sculpture teaching method by Artist Nathalie Miebach based on weather data collection.

“One layer of salt, one layer of fish.

All fish overlap and intertwine with each other.

According to tradition, fish heads are placed counterclockwise.

This is to show respect to customers.

The Matagi tribes are traditional winter hunters of the Tōhoku region of northern Japan. Because of the geographical conditions, the tribes had to hunt for survival. Their lifes are sustained through hunting, firing fields, and making wooden and basketry objects.

With the introduction of guns in the 20th century, the need for group hunting for bear has diminished, leading to a decline in Matagi culture.

These muzzles would be fitted to cattle to prevent grazing when crossing fields with crops. The bentwood model is a particularly well made and pleasing object and probably less irritating for the cow or bull to wear than the rope one.

Explore book: The Hard Life by Jasper Morrison

The photos are a fascinating account of the lives of indigenous ‘Marsh Arabs’, whose lives in the marshes of Iraq were devastated by large scale draining of their homeland by Saddam Hussein in the 1990s. After the fall of the regime the arid marshes were re-flooded when people broke through the embankments holding back the water. The return of the plants, animals and community to this unique landscape speaks of the resilience of people and environment to respond and be restored after ecological destruction and crisis.

First constructed in the marshes of what is now southern Iraq over 5,000 years ago, the ‘mudhif‘, the huge parabolic arched construction, is a unique local meeting place constructed entirely of reeds, straw and other natural materials.

The sape' is a traditional lute of the Orang Ulu. These indigenous ethnic are mainly the “Kayan” and “Kenyah” groups who settle near the rivers of Central Borneo. They are known for their traditional musical instrument, jatung utang (wooden xylophone), sape' (a type of guitar), sape' bio (single stringed bass), lutong (a four- to six-string bamboo tube zither) and keringut (nose flute).

We study material folk-cultures not to know the future but to widen our horizons, to understand that our present situation is neither natural nor inevitable, and that we consequently have many more possibilities before us than we imagine.

The film was captured in Ethiopia by Gordon Clarke of the Institute of Nomadic Architecture.

Extremely fascinating functional artifact:

Insect cage made in cycad leaf

via aguni archive

“The world of our experience is, indeed, continually and endlessly coming into being around us as we weave. If it has a surface, it is like the surface of the basket: it has no ‘inside’ or ‘outside’. Mind is not above, nor nature below; rather, if we ask where mind is, it is in the weave of the surface itself. And it is within this weave that our projects of making, whatever they may be, are formulated and come to fruition. Only if we are capable of weaving, only then can we make.” — Tim Ingold

Listen to the sounds: The Growth of Artifacts by Yannick Dauby

-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-

The blog post section claims no possession for the materials use, nor for the purpose of commercial use. Some of the contents are either depicted with the knowledge of the owner, or without, due to the unaccessible origin of the information. If you are the owner of the content, and forbid sharing, please do not hesitate to contact me. In any case, your content will always be credited, direct or indirectly.